This is a bit of a conference digest. First: reflections on third culture and its literature; second reflections on Dulwich college and ships (related, I swear) and third (unrelated, except to my life in a Humanities Center here at Goucher College) Rosi Braidotti's keynote.

First:

Oh, I was as happy as a clam in the session on Third Culture. Photo credits Anastasia Goana Go Ying Ying.

Anastasia Goana Go Ying Ying (middle) presented Sociological material on TCKs and superdiversity (Vertovec), on identity denial (in which one can curtain/screen off parts of one's identity selectively and to situational advantage) and "enoughness" (when is one of a place "enough" to claim that place's identity?). She noted the problem of being "called out" for inconsistent self-identification. Her accounts of interviews and surveys were succinct and vivid.

Jessica Sanfilippo Schulz (right) contrasted and compared TC and Transcultural, referencing the work of Arianna Dagnino, and analysing Allende, Messud and Baraouie (TCAs who write in languages other than English). Her work is essential in advancing TC analysis into comparative literature.

Both of these papers were great.

My paper was about the cloud theory thing (spoken of previously on this blog). Here I am !

The questions after the papers raised familiar issues: why this term, do we need it? asked Cathy Waegner.

I think we do . . . but it's only useful if it adds something specific not covered elsewhere: I still believe it does, though maybe the transcultural is coming awfully close.

Isn't this a (heinous!) biographically driven reading, asked a woman whose name I didn't record. Yes. It is. Thinking about this afterwards, I think the only way round this is to indicate forcefully that third culture literature has characteristics discernible in the literature. ie you can know TCL even if you don't know anything about the author's life. (please see my next book??)

Second:

I recently published an article on Michael Ondaatje in which I argue that Dulwich College in London, where he went to school ages 11-18, is a privileged enclave of white Britishness. En route to dinner at an old friend's house, said friend drove us past Dulwich College and talked about how it started as a school for the underprivileged, and persists as a place that heavily recruits international students.

Hmn. So, It is not what I thought, at all. Perhaps it is even more apropos though: as international school (like UWC or its ilk), Ondaatje would have been amongst other TCKs like himself.

Also Jessica had told me about Amitav Ghosh as a TCK, and she is doing great work on ships as a metaphor: I heard a wonderful paper (by Florian Stadtler) on Ghosh's trilogy (Sea of Poppies, River of Smoke, Flood of Fire): all very liquid and fluid and all that. Stadtler argues that the national is presented as negative, and the very specifically local as salvific. Stadtler lifts a term from cinema: "network narrative" (David Brodwell, Poetics of Cinema, 2008 p 243) to explain fluid synchronicities. I want to read the trilogy and return to his argument.

Third:

Braidotti on the Humanities.

OMG do we not care about analysing the human anymore? I was recently scolded for insufficient engagement (my whole center, the Humanities Center, was, not just me). How can we engage when the pasts of our disciplines are coming to an end and their futures aren't yet clear? Braidotti argues that we are on the cusp of a sixth extinction environmentally and an end-point disciplinarily. Speaking for literature alone: whither the future if everyone writes and no one reads ? (pun intended).

Is literature's saving grace that it teaches empathy in a tech-heavy individualistic world? Do we need war to bring back the importance of the human and of human stories?

Fiction, Poetry, Drama. The term itself is defined in this blog's first post: "What is Third Culture Literature?"

shelves

Monday, September 25, 2017

Wednesday, September 6, 2017

Aufwiedersehen British Army Brats in Germany (Guest Post: Jessica Sanfilipo Schulz )

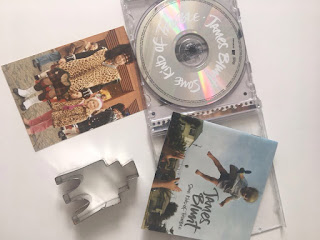

Whilst carrying

out research for a scholarly article I recently wrote about TCK songwriters, I

stumbled upon many musicians who grew up as military brats in Germany. A couple

of weeks ago I submitted the article but since then my list of artists who, as the

offspring of British Armed Forces personnel, were raised in Germany still seems

to be growing. Some of the musicians, for example, are James Blunt, Pete

Doherty and Colin Greenwood (Radiohead). Incidentally, Tanita Tikaram was born

in Muenster, where I am currently living. When my family and I first moved to

Muenster in 2003, the presence of the families of the British Armed Forces conferred

this otherwise very provincial town, an aura of internationality.

Originally, the units

of the British 21st Army Group arrived in Muenster in April 1945.

Soon after this, when Germany was divided into zones of occupation, the British

Army was assigned the north-western part of the country and more specifically

the key cities of Cologne, Dortmund, Duesseldorf, Hamburg, Bremen, Kiel,

Hannover, the Ruhr valley and the North Sea coast. Furthermore, the 21st

Army Group was renamed “British Army of the Rhine”. The group then consisted of

80,000 soldiers. In 1955 the allied military occupation of West Germany

formally ended and at the end of the sixties, 55,000 British Army soldiers were

stationed in Germany. With the official unification of former East and West

Germany and the signing of the Treaty on the Final Settlement with Respect to

Germany, the British Government announced a framework for “Options for Change”,

involving substantial cuts in the British Army of the Rhine. It was also

announced that the group of units would be renamed to British Forces Germany

(BFG). Finally, in 2011 the MoD make public the pull-out of the 20,000 remaining

troops in Germany, which is to be accomplished by 2020.

At the end of

2012, Muenster witnessed the closing of the BFG barracks and the withdrawal

from the town of 600 troops and their families. Looking back, it appears that

they not only handed down barracks, housing accommodation and bi-cultural

liaisons to the town of Muenster, but thinking of TCK artists such as Tanita

Tikaram, it seems that some of the individuals who were linked to the BFG left

their artistry behind to a wider audience.

Shelley Jones

cunningly looks into the connection between creativity and nomadic childhoods.

She interviews TCKs who chose creative careers in adulthood. These TCKS confirm

that they began engaging in creativity in order to express their displacement.

Lance Bangs, a

TCK filmmaker (an American military brat), reveals that in childhood, amidst

the frequent travelling, he felt like he was going to disappear so he turned to

filming as a form of keeping an anchored journal. Donna Musil, also an American

military brat filmmaker, reports to Shelley Jones that creativity gives

military kids a voice: “Many of these kids don’t have a voice when they’re

growing up,” she says. “It’s always what the military needs, what the foreign

service needs, what the missionaries need. So I guess that makes a lot of

artists, because you want to express yourself.”

Thus, as Donna Musil

points out, whilst growing up, many TCKs did not have a voice because they had

to follow the etiquette of their parents’ employers and represent their

parents’ nations in an honorable way abroad. Creativity gave a voice to many

military brats, such as Ian McEwan, Tanita Tikaram and the designer Nicholas

Kirkwood, who all spent part of their childhood in Germany. Now, after 70

years, the British Army troops are preparing to leave Germany permanently. Not

only are the troops involved in this withdrawal but their families too. The

military cuts and withdrawals evidently mean that less British Army troops and

their families will be sent abroad and fewer children will be raised as British

military brats. So does this step also represent the end of a generation of British

military brat artists and the fascinating artistic outcome of their transient

childhoods? Luckily there are many other subcategories of TCKs. Brian Molko of

the rock band Placebo, for example, is a business brat, whereas the designer

Tom Dixon is an EdKid (see Zilber for this term). It is therefore reassuring

that there are currently still many other groups of TCKs on the move and I am looking

forward to their future expressions of creativity.

by Jessica Sanfilippo Schulz

Works Cited

Jones, Shelley. “Does

a Nomadic Childhood Lead to a More Creative Life? Uprooted Kids.” Huck Magazine. 22 July 2015. http://www.huckmagazine.com/art-and-culture/uprooted-kids/

Zilber, Ettie. Third Culture Kids: The Children of

Educators in International Schools. Melton, Woodbridge: John Catt, 2009.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)